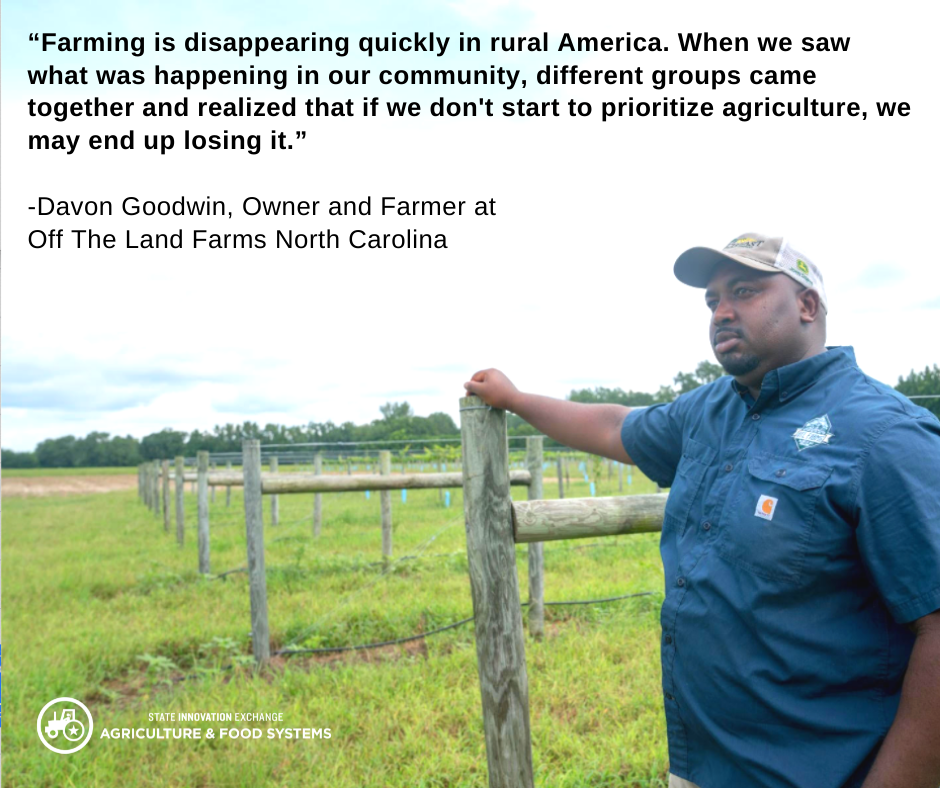

Davon Goodwin is a first generation Black farmer, a combat veteran and the owner/operator of Off The Land Farms located in Laurinburg, North Carolina. He produces muscadine grapes, blackberries and mixed vegetables on his 42-acre farm. Davon is also the director of Sandhills Ag Innovation Center, a local food hub that is an important component of the local sustainable agriculture and local food scene. This interview was conducted over zoom and has been shortened for length and clarity. This is part one of two. You can read part two here.

Photo credits: Davon Goodwin.

How is the work you are doing at Sandhills Ag Innovation Center helping to address some of the issues facing your community?

Sandhills Ag was created to not just help farmers farm, but to help them market and develop new crops and to support our community. Farming is disappearing quickly in rural America. When we saw what was happening in our community, different groups came together and realized that if we don’t start to prioritize agriculture, we may end up losing it. Our region is very poverty stricken and food insecurity is a big problem. We do a lot of work within the realm of food insecurity. Our communities have rates of high blood pressure, type two diabetes, obesity and other health problems. You often have traditional food banks that give soon-to-be expired or expired food and we felt that was not going to help our communities and their health in the long run.

Our model is about meeting our community where they are. When we started, we asked ourselves, ‘Okay, we know that we need to infuse our community with more fruits and vegetables so how do we do that in a way that doesn’t diminish the community?’ One of our solutions is to have a customizable CSA program that also gives farmers in the community access to another market, because we don’t want to waste food either. We want to make sure that we’re giving the community food that they are willing to eat while also introducing the community to a new fruit and vegetable every week, which can be a challenge. We have other challenges as well. This is our third year and it has been challenging because we’re losing farmers quicker than I think we realized. We have to move fast and we have had to shift the priorities of the facility to make sure we are reaching the needs of the community and our farmers.

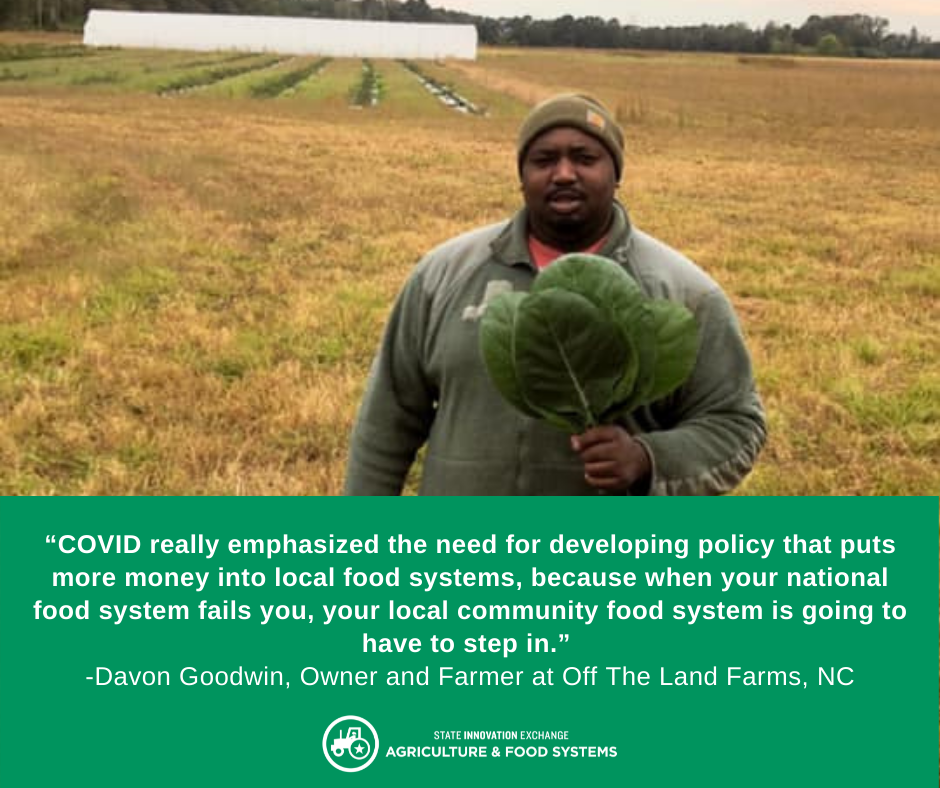

What has been the impact from COVID-19 on the work you are doing?

COVID was a gift and a curse. It shone a light on the fact that our national food system isn’t secure enough for our rural communities. COVID really emphasized the need for developing policy that puts more money into local food systems, because when your national food system fails you, your local community food system is going to have to step in. When there was a lack of food in grocery stores, our local farmers were there to meet the needs of our community. When it comes to policy, we need to infuse more money into our local food systems as well as build a more resilient system, because as we have seen in the last 15 months, our community was already in a bad position before COVID and it’s probably in a worse position now. When crises hit rural environments, which are already economically distressed, it makes every little existing problem more challenging.

How did you get into farming?

I didn’t get into farming in the traditional manner. I served in the Army for six and a half years. On August 31, 2010, my vehicle hit a roadside bomb in Afghanistan and it changed my whole life. Before that accident, I was a college student, studying biology and botany and the dream was to get a PhD in botany, and travel the world and do medicinal botany. From that blast, I suffered a traumatic brain injury and developed narcolepsy which put the dreams of being a researcher on the back burner, because it’s kind of hard to do research when you fall asleep. When I got back to the United States, I enrolled back into college at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, one of the largest agricultural counties in the state, but that same county has the largest food insecurity rate among children in the nation. It got me thinking, ‘how can we grow so much food, but be so hungry at the same time? You have all this land, but the people who are right next to the land have no food.’ So I became interested in that and thought about how I could address this issue. I had this crazy idea and said “You know what, I’m gonna be a farmer.” I thought it was going to be easy.

Well, I’m a city kid from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, so I had no clue what commercial agriculture looked like. After graduating, I found two doctors who had a 500-acre farm looking for a farm manager and they hired me and from there it was a whole whirlwind experience trying to figure out how we can grow good food at a cost that communities of color, especially, can afford. Fast forward to now, two years ago, my wife and I purchased the 42 acres in Laurinburg, North Carolina, which is home to Off the Land Farms. And so we’re on this journey to try to figure out how, as two city kids, we can move to a rural southern farm, raise kids and pay student loan debt, all while feeding our community good food. The banker said it was impossible, that there was no way we were going to be able to accrue this much debt and still have a philanthropic mission of feeding our community. But we consider ourselves a really big social experiment. If we can pull this off, it will not just be mind-blowing to us, but for our community, it’ll really mean something.

Can you talk about some of the challenges you face as a farmer?

One of things I want to do is encourage the next generation to farm. And it’s important as a Black person especially, because agriculture has not had a good story for people of color for the last 400 years. As a farmer and landowner, I’m rewriting that story and I get to dictate what happens in my story. Being a landowner is a new narrative that other farmers of color and I are getting to rewrite. When I look at farming, we’re getting to do it in the way we want to do it and we’re going to make sure our community always has access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Which is great — but from an economic standpoint, that’s going to be challenging. When you’re trying to grow sustainably, you have higher input costs and that cost has to go somewhere. We do advocacy work in our community so they understand that food will always cost money even if our policy doesn’t reflect that. In American policy we have bought into a cheap food policy. And it’s killing us. Last week, I had the chance to talk to the North Carolina Senate Agriculture Appropriations Committee and they talked about cheap food—they were glorifying the fact that we have cheap food. Maybe that’s the problem. Maybe we have not prioritized food enough. I look at my community, I think– how are we going to rewrite our story when policy is hurting us?

One of the big things impacting our farm right now is student loan debt. My wife is a nurse and she owes a little over $70,000 in student loan debt. That debt affects our farm every month, because that’s $1200 less that we can put into the business. I advocate a lot for student loan forgiveness for young farmers, because farming is public service. Being a first generation farmer, we’ve taken out over $400,000 just to start our farm. So I think when you look at public policy, it needs to be a different conversation around farming and how we want our society to be. Right now, we’re in a farm crisis. People don’t want to talk about it like that but we’re in it and if we don’t find a way to get more young people onto the land, we’re gonna have some hard times ahead. Some statistics say, we need over 100,000 farmers over the next two years. But look how much work that it takes to get one farmer into farming. Without some policy change, without some shift in the mindset or how we look at all of this, it’s just going to get more difficult in the future.

For some young farmers, the dream of farming will never come to fruition, because they will never be able to get over the barriers to land and capital. Every time a young person says they aren’t going to be able to make it in farming, that’s one less person you have to feed America. Right now, we don’t have a system where we can let one person go. So every time a young farmer can’t get into farming because they can’t access capital, or they can’t figure out how to farm, pay debt, feed their kids, and pay bills, it’s hurting us in the long run.

Check out the latest from Off The Land Farms here.